While a plethora of damages claims are regularly filed in front of jurisdictions in various countries of the European Union related to Article 101 TFEU (think, for example, the abundance of litigation against truck manufacturers), the same is not yet true for abuse of dominance cases. Notwithstanding that the Damages Directive is equally applicable to Article 102 TFEU cases, the number of (closed) dominance litigations is fairly limited, especially the ones in which a damage estimation was carried out in court proceedings. We are only aware of a few cases, including Cardiff Bus et Albion Water in the United Kingdom; Arzneimittelpreise et Wasserpreis der Stadt Mainz in Germany (although with relatively simplistic estimations). Notably, French courts seem to be rather open to estimate (and award) damages in dominance cases. See, for example the landmark case of Orange/Digicel or smaller cases like Le Berry Républicain/Aviscom.[1]

The fact that there are few dominance damages claims in front of national courts in Europe is not surprising for at least two reasons. First, dominance cases require (more) economic analysis from the competition authorities including, at least, an assessment of whether the company investigated is dominant in certain antitrust markets.[2] Second, the damage quantification in dominance cases is less straightforward than in cartel cases. However, as we show in this post with the example of the Google Shopping case of the European Commission (‘Commission’), a clear theoretical concept can be applied.

- Vertical foreclosure, theoretical framework[3]

The theoretical framework underlying damage calculations in abuse of dominance cases concerning vertical foreclosure can be demonstrated as follows. First, we need to clarify that one can only expect incentives to vertically foreclose competitors if a company is active both in the upstream and in the downstream markets, and at least on one of these markets the company is dominant. In this section we assume that, similarly to the Google Shopping case, the company is dominant upstream, and vertical foreclosure takes place.

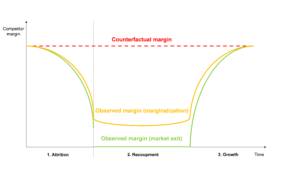

When the abuse begins, downstream competitors affected by the abuse start losing business, their margins are shrinking or even turn negative (attrition phase, see left hand side of Figure 1 below). The reduction of profits suffered by downstream competitors may lead to marginalization or a complete exit from the market. Both outcomes may lead to substantial financial damages. In this attrition phase, however, it is not clear whether there are adverse effects on consumers. If, for example, the attrition happens via the dominant company applying anti-competitively low (below-cost) prices, consumers may be better off for a while, as they pay lower prices. On the contrary, if the dominant company anti-competitively reduces rival firms’ demand by denying access to a large proportion of consumers (as it is likely in the case for Google Shopping), consumers are most likely negatively affected too. For example, consumers do not benefit from a larger number of available choices, and perhaps they become unaware of better deals.[4]

Figure 1 – Margin analysis for Article 102 TFEU damages cases, simplified framework

Source: modified version of Figure 2 in Fumagalli et. al. (2010)

The attrition phase is followed by a recoupment phase (middle part of Figure 1 above), during which the dominant company reaps the benefits of the successful foreclosure of competitors, by applying profit-maximizing monopoly prices in the downstream market (clearly harmful for consumers). By doing so, though, the dominant company encourages market entry at a later stage: this is called the phase of market growth, shown on the right hand-side of Figure 1 above. High margins may attract entry in the growth phase, but it is uncertain that the previously foreclosed competitors can re-enter or regain strength (in case they did not fully exited the market). Even so, they may not be able to supply as efficiently having lost out on profits during the preceding periods affecting, among other things, their ability to innovate or to realise economies of scale.

While it is not typical that all the three phases can be clearly distinguished in the case of an abuse of dominance, Figure 1 above represents the idea behind damages related to Article 102 TFEU cases.

Concerning damage quantification, the difference between cartel and dominance cases is also clear from Figure 1 above: while in cartel cases the counterfactual assessment focuses on but-for prices, when assessing damages in a dominance case the analysis is carried out on the counterfactual profits of the harmed competitors. Prices are still important in the context of a margin calculation, in which one can assess whether the damaged company could maintain a high enough margin to “survive” in the presence of the abusive behaviour.

- Application to Google Shopping

Turning to the Google Shopping case, the domains competing with Google Shopping can be entitled to damages based on the lost profits attributable to Google’s abusive behaviour (i.e., that Google’s algorithm demoted visibility of these product comparison websites). There are two main things to consider: (i) was the loss of profits attributable to Google’s anti-competitive behaviour; and (ii) what would have been the counterfactual level of profits of the competing price comparison websites?

- Loss of business

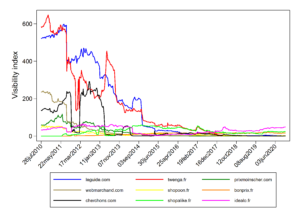

While it is the level of margins that matters, there are other metrics that can be used as indicators of profits (or losses) from running price comparison websites. One of these metrics is the Sistrix Visibility Index (which has also been used by the Commission in the Google Shopping decision[5]).

Based on Sistrix data, we generated Figure 2 below showing the Visibility Index of certain high-volume French comparison-shopping websites (domains are selected according to Graph 5 of the Google Shopping decision, the difference is that the lines below are shown to date). We use French data for demonstration, but visibility indices of other comparison websites from other countries show a similar picture.

Figure 2 – Sistrix Visibility Index for selected comparison-shopping services, France

Source: Sistrix.com

The reasons for showing the visibility indices to date are twofold: first, Figure 2 shows more evidently that Google’s demoting algorithm may have caused a long-lasting negative impact on almost all French price comparison websites included in the Commission’s analysis (successful attrition since at least October 2010 – the beginning of the infringement in France, according to the Commission’s decision). Second, it shows that the majority of these domains has practically zero visibility in the last 3-5 years. To understand the importance of the latter, first we need to understand the Sistrix Visibility Index.

According to the description on Sistrix’s website, the index measures the SEO (‘Search Engine Optimization’) success of over hundred millions of domains. SEO success depends on a number of factors that Google “crawls” to provide users the most relevant search results: website content, domain features, how often the website is updated, link features, social metrics (e.g., how many Facebook shares), etc.[6] The better the SEO, the better visibility the domain gets on the Google search result pages.

The Sistrix Visibility Index is based on search results obtained for a million keywords, weighted by search volume and click probability on the organic position (“[p]osition eight on a very high-traffic search term such as “nintendo switch” gives a higher value than position one on a low-traffic keyword such as “nintendo switch memory card recommendation” [7]). The results are accumulated for each domain and by country, and the Visibility Index is published daily.

The Visibility Index, in normal circumstances, is directly linked to the quality features of the websites. High Visibility Index implies high quality domains, and vice versa. If the Visibility Index is close to zero, it is because the website is insufficiently maintained by the owner.

Returning to Figure 2 above, we can observe that almost all French comparison websites have just above zero Visibility Index in the last 3-5 years, whereas in the beginning of the 2010s some of them had a Visibility Index as high as 300-600 (for comparison, French Amazon had a Visibility Index around 700-800 within the same time period). This may be an indication that, while the quality of comparison shopping websites was relatively high earlier (so that Google search provided them a high level of visibility), at a later stage they have provided very low quality information, so Google did not find them relevant to show to consumers. These websites do not provide competitive enough content any longer. Or so Google says. But is this true?

- Proof of a causal link

The question that arises with respect to the loss of visibility described above is to what extent Google’s abusive behaviour contributed to the loss. According to the Commission’s decision, Google’s conduct is “abusive because it […] decreases traffic from Google’s general search results pages to competing comparison shopping services and increases traffic from [..] to Google’s own comparison shopping service”[8] but it does not go further than suggesting that the conduct is “capable of having, or likely to have, anti-competitive effects in the national markets for comparison shopping services and general search services”.[9] However, the analyses carried out by the Commission based on Visibility Index and ranking data[10] implies that the abuse had negative effects on competition by anti-competitively foreclosing price comparison websites and, at the same time, artificially increasing visibility of Google Shopping.

Nevertheless, one could say that the loss of visibility may not have been fully attributable to Google’s anti-competitive algorithm, but rather it was due to a series of unrelated reasons including, for example, bad management of some of these price comparison websites through a wrong SEO strategy . While such “mistakes” by the managements of comparison websites cannot entirely be ruled out, it is highly unlikely that the Visibility Index dropped for so many comparison websites, across major markets in Europe, at around the same time because they suffered from bad SEO management. It is more likely that Google’s (Panda) algorithm demoted the visibility of these websites across the board, leading to a general “deprivation” of these domains by not having access to a high enough visibility in general Google search results. Regardless of whether the “deprivation” algorithm is still in place today or Google has already stopped the abusive behaviour (and perhaps it simply does not make business sense to (re-)develop these websites to increase SEO success), the outcome is likely to be linked to the abuse.

Establishing a link to the abusive behaviour, though, is only the first step. The second step is to assess the size of the damage.

- Counterfactual assessment

As it is now well established in cartel damages cases, typically there is a need for an estimation of a counterfactual market, that is, how the market would have evolved in a “counterfactual world” without the existence of a cartel. This can be done, for example, by comparing the cartelised market with other non-cartelized markets or with certain time periods of the same market that were not affected by the cartel (or a combination of the two).

Similar but-for scenarios are necessary for assessing damages cases related to abuse of dominance as well. That is, estimating margins of the claimants in a hypothetical market situation in which there was no abuse. This requires estimation of both counterfactual revenues and counterfactual costs. In damages claims related to the Google Shopping case, the difference between the observed and the but-for scenarios should be assessed empirically based on market data, business data sourced from comparison websites and from Google.

In the course of the damage calculations it is important that one distinguishes between the reduction in profits related to the abuse from the potential profit changes that would have been present in the counterfactual market as well, for example, due to an increase in demand for shopping online or an increase in the general competitive pressure in the comparison shopping services market over time.

Furthermore, counterfactual cost estimates should include an assessment of the relative efficiency of the competing comparison websites. Equally to the situation in which a competition authority investigates an abuse, it is the costs of the dominant company that matters in damages cases (and not the costs of the claimant). Even so, when estimating damages, Google’s costs related to running Google Shopping should be assessed as if Google Shopping was an independent service from other services provided by Google/Alphabet.

It is obvious that a claimant competitor should not be compensated for being inefficient. However, we expect that a significant part of the inefficiency of competitors compared to the dominant player is a direct result of the foreclosure by that dominant player (as it is likely to be the case in Google Shopping). Hence, a counterfactual assessment of profits should not only encompass the loss of actual profits but also how those profits would have been used had foreclosure not taken place in the market. This may be particularly relevant for fast growing markets like the tech sector where the inability to use lost profits due to anti-competitive behaviour of the dominant company is a crucial detriment to competition.

Nevertheless, anti-competitive effects and damages can arise both for equally efficient competitors as well as for less efficient competitors. The damage size, obviously, is expected to be less for the latter cases (assuming the inefficiency is not caused by the infringement itself).

By Akos Reger

[1] A summary of the methodologies applied by French courts can be found in Carval, Suzanne; Laborde, Jean-François, La réparation des prejudices causés par les abus de position dominante, Concurrences No 1-2018, Section 2.2.

[2] According to the case register, the European Commission published around 2.5 times more summary decisions in Article 101 TFEU cases.

[3] This part is based on Fumagalli, Chiara; Padilla, Jorge; Polo, Michele (2010), Damages for exclusionary abuses: a primer (full text available online at https://ec.europa.eu/competition/antitrust/actionsdamages/fumagalli_padilla_polo.pdf). See similar theories in Maier-Rigaud, Frank; Schwalbe, Ulrich, Quantification of Antitrust Damages, IESEG School of Management, Working Paper Series, 2013-ECO-09, June 2013, p30-35. (full text available online at https://www.ieseg.fr/wp-content/uploads/2013-ECO-09_Maier-Rigaud.pdf)

[4] With respect to the latter, there is an indication that prices of products displayed on Google’s Shopping Unit may have been higher than the prices of the same products on the website of competing price comparison websites. See the presentation of Grant Thorton available at https://images.politico.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Google-Shopping-EU-benchmark-study1.pdf.

[5] Commission Decision of 27 June 2017, Google Search (Shopping), Case AT.39740, para. 361.

[6] https://moz.com/learn/seo/what-is-seo#:~:text=SEO%20stands%20for%20Search%20Engine,through%20organic%20search%20engine%20results

[7] https://www.sistrix.com/support/sistrix-visibility-index-explanation-background-and-calculation/#Strengths_and_limits

[8] Supra note 5, para. 341.

[9] Supra note 5, para. 341.

[10] Supra note 5, Section 7.2.1.